Guaranteed to teach you things you never knew.

How Our Senses Trigger Memories - Part 2: Sound and Music (By Brian Levine Ph.D.)

Clinical neuropsychologist, Dr. Brian Levine, shares how sound and music affects our ability to trigger and recall memories.

"Music, at its essence, is what gives us memories. And the longer a song has existed in our lives, the more memories we have of it."

Stevie Wonder

Musical time capsules

Every time I hear the song “American Pie,” it brings me right back to the 1970’s when I was a kid listening to CKLW in Detroit. “American Pie” is a great song by any measure, but the reason it so effectively takes me back in time is coincidental rather than prosaic; it coincided with me figuring out who I am. If I had been born at a different time, some other song would have become the soundtrack of my awakening.

The satellite radio service Sirius XM has a channel for each decade from the 50s to the 2010s. Whoever created those channels understood something important about human memory, which is that our lives are indexed by cultural context. That is, the songs, movies, and events occurring in the period of identity formation (about age 15-30) are automatically imbued with life-changing significance. Sirius XM listeners can dial into those monumental life periods at will, no matter what their age. There are even channels that combine two decades for those of us whose coming of age wasn’t conveniently set in the middle of a decade.

The reminiscence bump and the intrinsic value of novelty

Memory fades exponentially with the passage of time (events from an hour ago are more vividly recollected than events of a day ago by about an order of magnitude, and vividness declines by a similar amount after the passage of a month, a year, 10 years, and so on…), except for things that happened in our teens and 20’s, which retain their vividness despite the passage of time. Memory scientists call this the “reminiscence bump.” The reminiscence bump is not just about music. Personal events, travels, world events, sporting events, movies and shows, and other contents from this period are generally better remembered than any other remote lifetime period.

Were things just better then? It may feel that way, but this can’t be true if everyone thinks that their era was the best. The late teens to the mid-twenties tend to be the period of greatest exploration, where we throw off the shackles of our childhood, see things anew, form new relationships, and experience losses and gains in new ways. Novel events can happen at any time, but more of them happen during the late teens and early twenties. By the time we are in our 30’s, it is already harder to have new experiences.

Learn more: Unraveling the Reminiscence Bump: A Deep Dive into Memory and Storytelling

The special role of music in evoking memory

Imagine going on a trip on your own or with a friend – without your parents – for the first time. What was playing? Was it the Beatles' Rubber Soul, Metallica, Taylor Swift’s 1989, Beyonce? Whatever it was, that event will be inextricably bound up with the surrounding context: location, a cast of characters, and whatever else was going on at that time – including the music that was in the air.

Recorded music is unique among these contextual cues because it can be reproduced precisely as it was in the first instance. As soon as I hear Don MacLean’s voice singing the words “A long long time ago, I can still remember…” I do remember. But more than memory, it's a feeling unique to a special time of my life.

In my previous article, I described the power of visual processes in memory, such as photographs. Photographs are – quite literally – snapshots that require us to supply emotional and mental associations if they are to cue a memory. Movies and video clips can drive memory retrieval for a longer time, but every filmmaker knows the power of music for evoking a feeling. (If you don’t believe me, try watching a scary scene in a movie with the volume down.) As our life’s soundtrack, the right musical selection can bathe us in feelings, priming associations to memories of self-defining events.

Using music to evoke memories

The types of songs described above evoke a lifetime period, but not necessarily a single event. If you'd like to use music to unlock recollections and stories from someone else, here are some tips on the selection of such musical cues to evoke past memories.

- Find out what songs your interviewee listened to during their teens and 20’s and play those songs.

- If you cannot harvest specific songs from the interviewee, select from among any list of hits from that time period (i.e., ask Google for the top 20 songs of the 1970s).

- Don’t forget about other time periods, especially if they are tied to an event. It’s not that songs from other periods can’t evoke memories, it’s just that they are less likely to do so.

- When they listen, give them the space to stop, think, and elaborate on the thoughts that come to mind. But make sure you get to the chorus, hooks, or other memorable parts of the song.

- Other cues, such as photographs (public or personal) from that time period can be helpful. But be careful not to overwhelm them. Sometimes a simple musical cue is best without any interference from other senses. You might be surprised at what comes up.

- These songs may cue a lifetime period, but not necessarily a specific event. So be prepared to ask followup questions to help the person select events.

- Musical cues can be effective in people with dementia, who have difficulty accessing memories through a self-initiated search.

- Some songs cue memory for specific events (e.g., the first dance at a wedding). In that case, your job is easy; just use that song as a musical cue for that event.

Memory is multimodal. This the second in a series of articles about senses and memory. The first article focused on the power of visual memory.

About Brian Levine PhD

Dr. Brian Levine is a clinical neuropsychologist and senior scientist at the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest and a Professor of Psychology and Medicine (Neurology) at the University of Toronto, where he leads a lab conducting research on the cognitive neuroscience of naturalistic memory and attention.

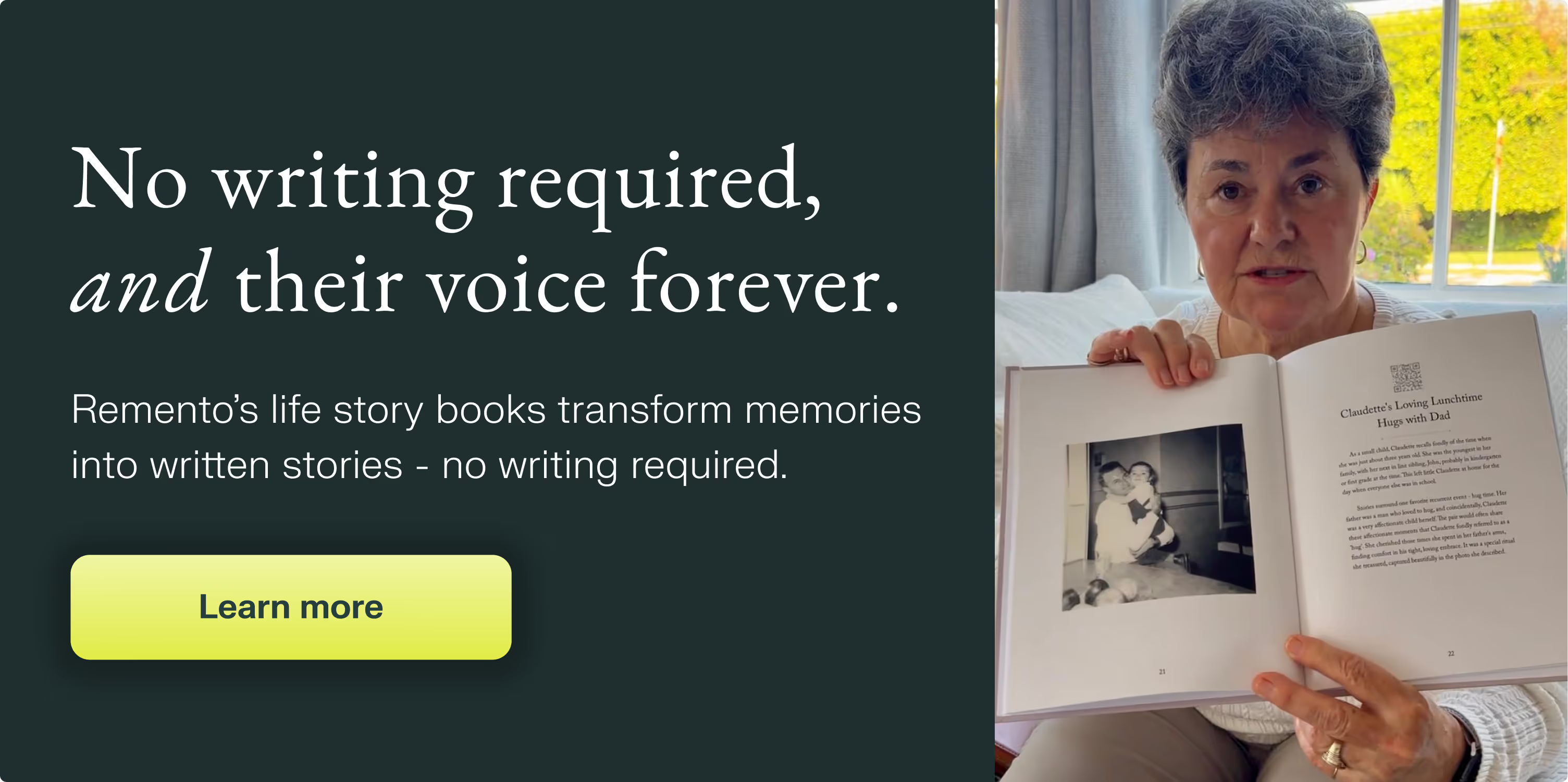

Their stories, forever at your fingertips

Remento’s life story books turn a parent or grandparent’s memories of the past into a keepsake book for the future - no writing required.

Capture priceless family memories today

Join the thousands of families using Remento to preserve family history, all without writing a word.

.avif)